The Peaceful Albin?

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5!?

Black strikes back in the centre in violent uncompromising fashion. You'll never take me alive, he protests, stamping his boot and shaking his fist. Thus the Albin!

I grew up in love with this risque counter to the Queen's Gambit. A kid played it against me once in a scholastic tournament and I was enthralled. That first game was not very interesting. I followed up 3. cxd5 and the position quickly smoothed over into flat equality... though I eventually prevailed! My life would never be the same again, however. I found a musty old copy of Lamford's book on the gambit and started to employ it whenever I encountered a d-pawn player. At one point my USCF record with the gambit was a startling 8 for 8 with the black pieces! Every trap in the opening seemed to work like it was a foregone conclusion. I won a sweet little game that went:

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5 3. dxe5 d4 4. e3 Bb4+ 5. Bd2 dxe3 6. Bxb4 exf2+ 7. Kxf2 Qxd1 8. resign

Yes, I was a weak player back in those days, but ahhh, it was nice when opponents used to hand out shrink-wrapped wins on silver platters like that. In any case, the heart of the Albin lines according to the books go:

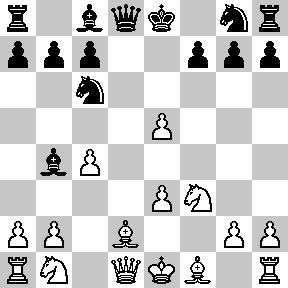

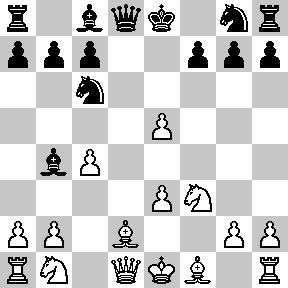

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5 3. dxe5 d4 4. Nf3 Nc6 5. g3

White accepts the gambit and both sides play with extended pawns that impinge somewhat uncomfortably on the opponents' position. Black is down a pawn, but in return gets dynamism, a semi-open game that is more reminiscent of many e4 systems or of the Benoni than of most d4 lines and attacking chances against the white kingside. It all sounds great, right?

The main followup plans involve either moving the queenside bishop or the kingside knight. 5. ... Nge7 is Russian Superstar Alexander Morozevich's patent, a move that seems to be taking off after it appeared in the Secrets of Opening Surprises series and was featured in several of Nakamura's games. It is a little more solid than the more traditional bishop moves, eg. 5. ... Bf5, Be6, and Bg5. Each of these moves has its advantages and short-comings, but I never had much trouble in these main line positions with black. I always found that the inherent aggression of the pawn structure worked to my advantage, even when White managed to combine aggressive pawn advances with the long-range power of the fianchettoed bishop. Much more troubling, believe it or not, has always been the annoying patzer move 5. a3!? Here white forgoes rapid development in an effort to avoid the bishop check on b4, enabling the undermining advance e3. The amazing bit here is the difficulty that black faces achieving anything more than a miserable equality. I will also note here that I have had stunning difficulties after 5. e3 Bb4+ 6. Bd2 dxe3 7. fxe3.

It can be amazingly difficult to take advantage of the doubled pawns if there is an exchange of queens. Additionally, if white can maneuver a piece to d4 without losing the advanced e5 pawn, good luck securing any advantage...

It can be amazingly difficult to take advantage of the doubled pawns if there is an exchange of queens. Additionally, if white can maneuver a piece to d4 without losing the advanced e5 pawn, good luck securing any advantage...

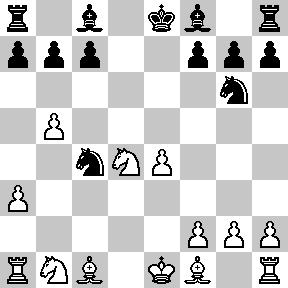

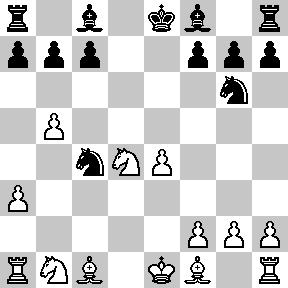

Chris Ward's recent book on Unusual Queen's Gambits offers 5. a3 Nge7 as an interesting departure from the relatively lame 5. ... Be6, but though this stands up alright against 6. e3, I have found it to be somewhat wanting against 6. b4!? a move that I have never seen in any book on the subject. It looks a little silly I know, another patzer idea at work - push the b-pawn down the board to kick away the defense of the d-pawn, but it is very annoying. Play continues something like: 6. ... Ng6 7. b5 Ncxe5 8. Qxd4 Qxd4 9. Nxd4 Nxc4 10. e4.

The question is, can black develop counterplay against white's stronger central grip? The answer is probably, but it's certainly no picnic. Black has to retreat his knight and white will have a lot more space.

The question is, can black develop counterplay against white's stronger central grip? The answer is probably, but it's certainly no picnic. Black has to retreat his knight and white will have a lot more space.

I think this is the most irritating thing in the whole Albin complex, and is most certainly the main thing that has turned me off to playing the Albin in recent years. It's really too bad from a competitive standpoint, because all of the other Albin lines are fun to play... Does anyone have suggested improvements? Has there ever been any high-level analysis of this line?

Black strikes back in the centre in violent uncompromising fashion. You'll never take me alive, he protests, stamping his boot and shaking his fist. Thus the Albin!

I grew up in love with this risque counter to the Queen's Gambit. A kid played it against me once in a scholastic tournament and I was enthralled. That first game was not very interesting. I followed up 3. cxd5 and the position quickly smoothed over into flat equality... though I eventually prevailed! My life would never be the same again, however. I found a musty old copy of Lamford's book on the gambit and started to employ it whenever I encountered a d-pawn player. At one point my USCF record with the gambit was a startling 8 for 8 with the black pieces! Every trap in the opening seemed to work like it was a foregone conclusion. I won a sweet little game that went:

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5 3. dxe5 d4 4. e3 Bb4+ 5. Bd2 dxe3 6. Bxb4 exf2+ 7. Kxf2 Qxd1 8. resign

Yes, I was a weak player back in those days, but ahhh, it was nice when opponents used to hand out shrink-wrapped wins on silver platters like that. In any case, the heart of the Albin lines according to the books go:

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e5 3. dxe5 d4 4. Nf3 Nc6 5. g3

White accepts the gambit and both sides play with extended pawns that impinge somewhat uncomfortably on the opponents' position. Black is down a pawn, but in return gets dynamism, a semi-open game that is more reminiscent of many e4 systems or of the Benoni than of most d4 lines and attacking chances against the white kingside. It all sounds great, right?

The main followup plans involve either moving the queenside bishop or the kingside knight. 5. ... Nge7 is Russian Superstar Alexander Morozevich's patent, a move that seems to be taking off after it appeared in the Secrets of Opening Surprises series and was featured in several of Nakamura's games. It is a little more solid than the more traditional bishop moves, eg. 5. ... Bf5, Be6, and Bg5. Each of these moves has its advantages and short-comings, but I never had much trouble in these main line positions with black. I always found that the inherent aggression of the pawn structure worked to my advantage, even when White managed to combine aggressive pawn advances with the long-range power of the fianchettoed bishop. Much more troubling, believe it or not, has always been the annoying patzer move 5. a3!? Here white forgoes rapid development in an effort to avoid the bishop check on b4, enabling the undermining advance e3. The amazing bit here is the difficulty that black faces achieving anything more than a miserable equality. I will also note here that I have had stunning difficulties after 5. e3 Bb4+ 6. Bd2 dxe3 7. fxe3.

It can be amazingly difficult to take advantage of the doubled pawns if there is an exchange of queens. Additionally, if white can maneuver a piece to d4 without losing the advanced e5 pawn, good luck securing any advantage...

It can be amazingly difficult to take advantage of the doubled pawns if there is an exchange of queens. Additionally, if white can maneuver a piece to d4 without losing the advanced e5 pawn, good luck securing any advantage...Chris Ward's recent book on Unusual Queen's Gambits offers 5. a3 Nge7 as an interesting departure from the relatively lame 5. ... Be6, but though this stands up alright against 6. e3, I have found it to be somewhat wanting against 6. b4!? a move that I have never seen in any book on the subject. It looks a little silly I know, another patzer idea at work - push the b-pawn down the board to kick away the defense of the d-pawn, but it is very annoying. Play continues something like: 6. ... Ng6 7. b5 Ncxe5 8. Qxd4 Qxd4 9. Nxd4 Nxc4 10. e4.

The question is, can black develop counterplay against white's stronger central grip? The answer is probably, but it's certainly no picnic. Black has to retreat his knight and white will have a lot more space.

The question is, can black develop counterplay against white's stronger central grip? The answer is probably, but it's certainly no picnic. Black has to retreat his knight and white will have a lot more space.I think this is the most irritating thing in the whole Albin complex, and is most certainly the main thing that has turned me off to playing the Albin in recent years. It's really too bad from a competitive standpoint, because all of the other Albin lines are fun to play... Does anyone have suggested improvements? Has there ever been any high-level analysis of this line?

3 Comments:

Wait until you see that position 3 times, by 3 different opponents. Until then give yourself permission to play ALBIN ! IF in 100 games, you only get that position you don't like 5 times, then keep playing the albin. Is easier to remember the 1 guy and his name, who knows what to do vs it than to learn a whole new opening. And against this 1 guy, you just play something more positional, annoying the theory guy, by taking him out of book early.

Very often we play over lots of lines in book and FORGET that opponent will not think the same way about the same positions we've been looking at. There is no guarantee that by the time our opponent actually faces the albin, already to trot out that line, that he gets excited and mixes up the moves; or even worse plays it exactly -- then becomes overconfident thinking theory will win the game by itself (it won't, there is always tactics, endgame, move to move play that happens before the theoretical advantage can be realized) then you just play it cool, move quickly and confidently, and he'll try to vary, fearing an improvement

And if you lose the game... well you let the other players think they can play this line against you too-- then you switch them up with another opening, then you comeback to albin when they aren't expecting it -- about 6 months later is good amount of time for them to forget

Trouble is, the line is actually quite popular...

Wait until you see that position 3 times, by 3 different opponents. Until then give yourself permission to play ALBIN ! IF in 100 games, you only get that position you don't like 5 times, then keep playing the albin. Is easier to remember the 1 guy and his name, who knows what to do vs it than to learn a whole new opening. And against this 1 guy, you just play something more positional, annoying the theory guy, by taking him out of book early.

Very often we play over lots of lines in book and FORGET that opponent will not think the same way about the same positions we've been looking at. There is no guarantee that by the time our opponent actually faces the albin, already to trot out that line, that he gets excited and mixes up the moves; or even worse plays it exactly -- then becomes overconfident thinking theory will win the game by itself (it won't, there is always tactics, endgame, move to move play that happens before the theoretical advantage can be realized) then you just play it cool, move quickly and confidently, and he'll try to vary, fearing an improvement

And if you lose the game... well you let the other players think they can play this line against you too-- then you switch them up with another opening, then you comeback to albin when they aren't expecting it -- about 6 months later is good amount of time for them to forget

Post a Comment

<< Home